We eat lots of kinds of food in Sweden.

Husmanskost is the name of the most regular dishes. Only at the weekends

we make a "big" dinner. Then the ingredients are more

expensive and we make it more exclusive. At feasts we have traditionel

dishes like dop in the pod and surströmming (fermented baltic herring).

Swedish food traditions

Genuine Swedish food- Is there such a thing? Sweden has

a fine old culinary tradition. The Swedish husmanskost, good old

everyday food based on classic country cooking, has been influenced by

foreign cuisine over the years. Basically it is genuinely Swedish. Today

the plain and hearty husmanskost is undergoing a renaissance in Sweden.

The best of the old recipes have been revived and often revised so they

are less sturdy and easier to prepare. Propaganda for better diets has

also helped to improve the Swedish husmanskost, reduct the fat content

and add fruits and vegetables.

Regional Specialties

In Sweden everybody has about the same food habits and

customs. Many provinces have a reputation for special food. On the

eastcoust the most important food is strömming (Baltic herring). That

is a small silvery fish. Salmon, trout and whitefish are other important

fishes. Norrland, the nine northern provinces of Sweden has a lot to

offer. In Lappland you must try the dark gamy reindeer meet and åkerbär,

the rare berry that grows wild along roadsides and ditches. The åkerbär

looks like a small raspberry. The hjortron or cloudberry is another fine

Norrland fruit. Two Norrland provinces, Västerbotten and Norrbotten are

famous for their dumplings, palt. They are made of raw as well as cooked

potatoes, flour and salt, and served with butter and lingonberries.

Other Norrland specialties are tunnbröd, the thin white crispbread, and

långmjölk (sour milk).

The Swedish smörgåsbord

The Swedish smörgåsbord is world famous. You can have

it in IKEA in Milano and London. Today, the traditionell large smörgåsbord

with its lavish of food can be found only in a few resaurants, usually

at Christmastime. Once in a while, mostly in rural areas, the complete

old-time smörgåsbord will be prepered. when you meet with a smörgåsbord

of this kind. it's important to know the rules for how to approach it,

or it may become just a hotch-potch of flowers and impressions. The

commonly accepted and best way of enjoying the large smörgåsbord is to

eat each kind of food separately it is deemed necessary.

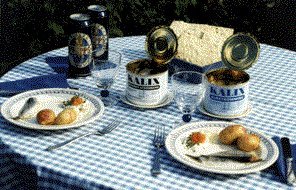

Crayfish and surströmming

Sweden has an extensive coastline and many lakes, so it´s

not surprising that fish plays a major part in the country´s diet. On

the west coast the specialties are shellfish, fresh mackerel and cod.

The crayfish season starts around August 8, and continues for about six

weeks. It is taken quite seriously in Sweden, when the nights are long

and the parties, floating on aquavit, run on into the twilight. The

small, black, freshwater crustaceans are dropped live into boiling

salted water with a huge bunch of dill; during cooking their color

changes to a bright red. A speciality of northen Sweden, surströmming,

is for sale from the third Thursday in August. To serve surströmming

the proper way: · Tie a napkin around the can · Place it on the table

· Then carefully open the can · A strong odor will at once reach your

nostrils and fill the room

"Beginners" often need some time to get used to the unique

smell of surströmming, some even go so far as to call it a stench. You

serve surströmming with potatoes, sourcream, onoin and white crispbread.

Feast food in Sweden

At Christmas in Sweden we often start with eating a

buffet-style. The buffet- style are filled with a lot of heavy dishes

both hot and cold. Ham, meat- balls, different salads and a lot of other

food. We also eat Dip in the pot when we eat a smörgåsbord, which is

slices of rye bread which are immersed in hot bouillon and then enjoyed

together with ham, pork, sausage or butter. Often after the buffet-style

comes the Santa Claus with gifts. After the Santa Claus it is time for

the traditional Christmas supper-lutfisk and creamed rice.

On Easter Eve we in Sweden eat a small smörgåsbord

and boiled eggs are seldom missing. The smörgåsbord consists of ham,

different herring, fresh salmon, eggs and a lot of different things. At

midsummer we eat sometimes a small smörgåsbord, but mostly we eat

boiled new potatoes, herring and a fresh green salad. And as a dessert

we eat strawberries with whipped cream.

Why don't you try a Swedish-recipe!?

Janssons Frestelse (Jansson's Temptation)

6 to 8 potatoes 2 onions 2 to 3 tablespoons margarine or butter 1 to 2

cans anchovy fillets 2½ to 3 dl (1 1/4 to 1½ cups) light cream

Peel the potatoes, cut in thin sticks. Slice the onions. Sauté the

onion lightly in some of the margarine or butter. Drain the anchovies

and cut in pieces. Put the potatoes, onion and anchovies in layers in

buttered baking dish. The first and last layer should be potatoes. Dot

with margarine or butter on top. Pour in a little of the liquid from the

anchovies and half of the cream. Bake in a 200 C oven for about 20

minutes. Pour in the remaning cream and bake for another 30 minutes or

till the potatoes are tender. Serve as a first course or supper dish.

Kalops (Swedish Beef Stew)

1 kg beef with bones or 600 g boneless beef: rib, rump

brisket or buttom round. 3 tablespoons margarines or butter 3

tablespoons flour 1½ teaspoons salt 2 onions, sliced 1 bay leaf 10

whole allspice 4-5 dl (1 3/4 to 2 cups ) water

Cut the meat in large cubes. Heat the margarine or butter in a heavy

saucepan. When the foan subsides, add the meat and brown it well on all

sides. Sprinkle with the floor and salt. Stir the meat. Add the onions,

bay leaf, allspice and water. Cover and simmer till tender, 1 ½ to 2

hours. Serve with boiled potatoes, pickled beets and tossed salad.

Here is an article about safe food production in Sweden

from Sweden.org:

|

|

A new Swedish model:

safe, clean food

|

|

by Stephen Croall

|

|

Sweden is making a name

for itself in Europe as a producer of clean, risk-free food -

safe meat and poultry, untainted dairy products and ecologically

grown* vegetables, potatoes and grain. In the wake of such

international food scares as mad cow disease and the dioxin

poisoning of chicken and egg products, consumers have grown

increasingly safety-conscious, and Swedish farmers and food

companies are now emphasizing their ecological profile in the

market.

Spurred by government incentives, the big farming and consumer

organizations are at the forefront of moves towards a new kind

of Swedish model, based on humane animal husbandry and `the

world's cleanest agriculture'.

Sweden has fought in the EU to keep its stringent rules on

things like salmonella checks and antibiotics in feed and has

been granted exemption in a number of instances. In fact, the EU

appears to be increasingly interested in the `Swedish model' as

a possible way forward for European food production as a whole.

|

|

Sweden is making a name for itself in Europe as a

producer of clean, risk-free food - safe meat and

poultry, untainted dairy products and ecologically

grown* vegetables, potatoes and grain. In the wake of

such international food scares as mad cow disease and

the dioxin poisoning of chicken and egg products,

consumers have grown increasingly safety-conscious, and

Swedish farmers and food companies are now emphasizing

their ecological profile in the market.

Spurred by government incentives, the big farming

and consumer organizations are at the forefront of moves

towards a new kind of Swedish model, based on humane

animal husbandry and `the world's cleanest agriculture'.

Sweden has fought in the EU to keep its stringent

rules on things like salmonella checks and antibiotics

in feed and has been granted exemption in a number of

instances. In fact, the EU appears to be increasingly

interested in the `Swedish model' as a possible way

forward for European food production as a whole.

In Sweden, public consciousness about the connection

between animal and human health in the food chain was

rudely awakened as early as 1953. A salmonella epidemic

thought to have originated in a slaughterhouse killed

almost 100 people. Shocked, the authorities clamped down

and in 1961 passed detailed new laws designed to prevent

salmonella from spreading to humans. Mainly as a result

of this early start, Sweden is today able to produce

chicken, eggs, pork and beef that are virtually

salmonella-free.

It was not until the 1980s, however, that

environment issues in general - ecological food

production among them - became a major focus of

attention in Swedish society. People began to discuss

not only the health aspects of food products but also

the ways in which they were produced. Interest grew in

the ecological and ethical aspects of Swedish

agriculture - what condition was farmland in and how

were farm animals being treated?

At the beginning of the decade, ecological farmers

were few and far between. There was virtually no

coordination of supplies, and these were largely

restricted to flour, potatoes and vegetables. Most

produce was sold directly from farmers to consumers on a

local basis, often through channels set up by the

consumers themselves or through health food stores. The

major food chains showed little interest in such

products. The few regular grocery shops that stocked

ecologically grown produce tended to put it in a corner

without any advertising, almost as a curiosity.

Growth of the ecological market

Consumer interest steadily grew, however, and market

conditions started to change. Growers began to organize

and major retailers and food manufacturers, unused to

dealing with numerous small suppliers, pressed for a

whole new distribution system for ecological products.

The first of three nationwide ecological producer

cooperatives was established, Samodlarna, specializing

in fruit, vegetables and potatoes. It was followed (in

the early 1990s) by Eco Trade, specializing in grain and

oilseeds, and Ekokött, which coordinated and developed

marketing channels for ecological meat.

But how were consumers to know that the produce was

in fact ecological? And what exactly did `ecological'

mean? There was considerable confusion on both counts

until the establishment in 1985 of KRAV, an inspection

body for certification accredited to both the Swedish

Board of Agriculture and the National Food

Administration. Together with that of the much smaller

Demeter, a certifying body for biodynamic farmers, the

green KRAV label soon became synonymous with clean,

safe, ecologically grown food in Sweden. Basically, the

purpose of KRAV and Demeter inspection and certification

is to ensure the credibility of ecological produce and

guarantee ecological products throughout the food chain

from farmer to consumer.

KRAV, which today claims to be the biggest

certifying organization of its kind in the world,

defines ecological products generally speaking as those

that have been produced without the use of aids like

chemical fertilizer or pesticides, or in the case of

poultry, meat and eggs, etc, without the use of

antibiotics, hormones and the like by livestock farmers.

Feed must be ecologically grown and farm animals must be

properly treated.

Nowadays, the organization and its label are so

widely accepted that most Swedes no longer refer to

`organic food' or `ecological food' but simply to `KRAV

food'.

Animal welfare in focus

As ecological awareness grew in the 1980s, animal

welfare in food production also attracted increasing

attention. The debate focused on large-scale husbandry

methods that led to sick and stressed animals,

particularly pigs and battery hens, and brutal handling

in connection with transports and slaughter. The fact

that many cows were being kept indoors all year round

came as a surprise to the general public and helped fuel

the animal rights debate, which was led by Astrid

Lindgren, the well-known and highly popular author of

children's books.

The use of growth drugs in livestock farming was

also strongly criticized. The public found it hard to

accept that healthy animals should be plied with

antibiotics. Farmers' organizations backed down and in

1985 a new law put a stop to the general practice of

adding antibiotics to feed for pigs, poultry and calves.

The use of drugs to improve feed efficiency for cattle

has never been allowed in Sweden.

Limiting farmers' access to drugs like antibiotics

also has repercussions for animal welfare. When

producers are unable to use them to cover up poor

management and an inadequate environment they have to

improve both if they want their animals to remain

healthy. Thus they have to identify and resolve the

causes of problems instead of simply treating the

symptoms with medication.

Following revelations that grass-eaters like cattle

and sheep were being given feed made from the carcasses

of sick animals, including destroyed pets, and from

condemned offal from slaughterhouses, a 1986 law forbade

the use of such feed for all animals in the human food

chain - a unique move that stood Swedish milk and beef

producers in good stead when the causes of mad cow

disease were established in the 1990s.

Spread of ecological farming

With a new Animal Protection Act in place, emphasizing

healthy livestock in natural surroundings, along with

other legislation of importance from an environmental

viewpoint, the 1990s have largely been a time of

ecological consolidation for Sweden's food producers and

consumers.

The decade began with a sudden leap in the amount of

ecological farmland, due both to a new government

subsidy for conversion to ecological agriculture and

burgeoning interest among food retailers. The proportion

of farmland turned over to ecological use rose from 0.5%

in 1989 to 3.5% in 1995. In that year, a new

comprehensive package of subsidies for ecological

conversion was introduced as part of the EU's

environment programme, and the Government announced an

official 10% goal for ecological farmland by the turn of

the century. This helped boost the figure to 8.6% by

1998 and although the goal does not look like being

achieved on schedule, it has been generally welcomed as

a way of focusing the agricultural mind.

Interestingly, the powerful Federation of Swedish

Farmers (LRF), traditionally the chief spokesman for

conventional farmers, is one of the organizations to

have thrown its weight behind the swing to ecological

farming.

At the end of 1998, KRAV had certified 2,860 farmers

and 127,000 hectares - as well as 580 retail shops, 570

processors and importers, 190 restaurants and industrial

kitchens, 17 textile processing companies and 2,700

products, 900 of them imported.

However, the increase in ecological farmland has not

resulted in a corresponding increase in ecological food

production. This is because much of the ecological

acreage comprises pasture and feed-crops not immediately

connected with the ecological food market. In 1997, for

instance, about 7% of Sweden's agricultural land

qualified for the ecological farming grant but less than

half of the land (3.4%) was actually certified by KRAV

or Demeter as being suitable for ecological food

production.

Nevertheless, a range of ecological food products is

now to be found in virtually every Swedish grocery

store, and most retail chain stores offer fresh produce

carrying the KRAV label. In some cases, stores have made

ecologically-certified food their competitive edge,

while others have restricted their involvement to

grudging compliance with consumer demands or general

company policy. Increasingly, however, an ecological

profile is being viewed in the Swedish food retail trade

as being not only potentially profitable but possibly

essential to the survival of the business in the long

term.

Consumer pressure increases

In June 1999, the consumer-owned Green Konsum chain - a

division of the giant retail cooperative movement, KF -

announced that it had doubled sales of ecological food

over the past two years and that by the end of the year

one item in ten on its shelves would be certifiably

ecological. At the same time, it claimed that the food

industry was holding up ecological development. Demand

was 2-3 times as great as supply, and the cooperative

was now having to build up its own production chains to

ensure that sought-after foodstuffs were constantly

available, particularly meat.

Green Konsum, with its 435 shops, is the biggest

ecological food retailer in Europe. It has become

increasingly critical both of the domestic food

industry, which it says is dominated by too few players

in near-monopoly positions, and of the Government, which

it says is too passive in its support. It has warned

that farmers may not be prepared to convert to

ecological production if industry is not geared to

receive what they produce, and that consumers may tire

of shortages on the shelves and withhold their custom.

For several years now, both KF and the

merchant-owned ICA chain have had their own ecological

brands on the shelves: KF's Änglamark brand and in the

case of ICA the Sunda brand for food and Skona for

technical-chemical products. Green Konsum make a point

of placing ecological fruit and vegetables on the same

counter as conventional products and marking them

clearly overhead.

Today, ecological food production in Sweden has

developed beyond primary products like fruit and

vegetables and processed products like milk, flour and

bread to even more refined products such as cheese, baby

food, ice cream, meatballs and jam. Ecological food

usually costs considerably more than equivalent

non-ecological products, but many people seem prepared

to pay. And as competition increases, prices are

expected to fall.

Safe Swedish Food on the Net

Ecological exports are steadily increasing, and the

Swedish food industry is showing particular interest in

places like Britain, Germany and the Benelux countries

where food safety is a major issue.

In early 1999, a new model for farm foods was

presented in Britain, the Swedish Farm Assured programme,

which allows British consumers with access to the

Internet to follow the item from the farm through the

production and transportation stages all the way to the

store shelf. Via a web address on the label, consumers

click their way to the (quality-certified) farm in

Sweden from where the product originated.

The programme currently involves some 40 milk and

pork producers whose entire output is intended for the

British market. Similar programmes are being developed

for other European markets, especially Germany, where

consumers are both environment-minded and well-informed.

Such export campaigns are reflected at home by

efforts to develop and introduce overall quality

assurance and environmental performance plans for

agriculture. The key points are traceability, high

quality and explicit environmental reporting, and the

plans incorporate both ISO 9002 and ISO 14001

certification, international standards that are accepted

in the export market and which the food processing

industries themselves use.

Such plans have already been introduced by exporters

of such items as cereals and grains (Swedish Seal), pork

and beef from slaughterhouses (Best In Sweden, BIS) and

vegetables and potatoes (Integrated Production, IP). An

environmental bonus or premium system has also been

implemented for milk production among dairy companies.

Down on the farm

The process of certifying quality begins at home with a

do-it-yourself inventory or annual checklist, known as

the Eco Audit. Farmers fill in a computerized form that

besides showing where they stand in environmental and

animal welfare terms also allows them to keep in touch

with the ever-changing laws and regulations that apply

to agriculture.

The authorities do not of course accept this kind of

self-inspection as being incontestably accurate, and

also carry out their own checks at the farm. But Eco

Audits are considered an important aid to marketing as

well as a money-saving incentive to producers, in that a

growing number of local authorities are reducing their

regulatory visits and charges as a result.

Completion of an Eco Audit is also increasingly

viewed by the food processing industry, especially the

dairies, as a precondition for cooperating with the

farmer in question, and the audits are an obligatory

part of quality programmes run by KRAV, Swedish Seal and

the slaughterhouses.

KRAV certification

KRAV, the major certifying body for ecological products,

is run as a non-profit organization. Any company,

association or other body operating on a nationwide

basis may become a member. The present 24 member

organizations include the big farming and retail

cooperatives, distributors, food processors and animal

protection groups as well as environmental groups that

were instrumental in launching the ecological movement

in the first place.

Internationally, KRAV is an active member of IFOAM,

the International Federation of Organic Agriculture

Movements, an umbrella organization uniting farmers,

scientists, educationalists and certifiers from most

parts of the world. KRAV takes an active part in

developing the IFOAM standards and also works to

influence EU legislation on ecological production. A

subsidiary, KRAV Kontroll AB, monitors KRAV-certified

production abroad, including textile processing and

fish-farming. A former KRAV subsidiary, the Grolink

consultancy firm, specializes in establishing

certification programmes abroad, particularly in the

developing countries.

At home, KRAV inspectors visit member companies and

organizations at least once a year to ensure that they

are complying with the regulations. In the case of

imports, KRAV's policy is to approve only products that

have been certified by other bodies accredited to IFOAM.

The major difference between KRAV and similar

organizations outside the Nordic area is that it also

embraces ecological livestock farming, taking into

consideration such ethical aspects as the animals' need

to live freely and naturally as far as possible. Today,

all cows in Sweden must be out in pasture in summer and

all pigs are allowed to roam loose. Calves and pigs must

have access to straw and reasonable space, and Sweden

has become the first EU country to outlaw battery cages

- hens must now have access to a nest, a perch and a

dustbath.

Antibiotics and hormes

The National Food Administration is the central

regulatory authority for food matters, and one of its

tasks is to protect consumer interests by working for

safe food. Its 1998 report showed that Swedish

foodstuffs are almost completely free from unwanted

substances like antibiotics and hormones. Of 16,000

samples taken from red meat, chicken, milk, fish, deer

and game, eight samples of beef and pork and only one of

milk contained antibiotic levels above the limit. None

contained hormone residues. In 1999, analysis is being

extended to honey and eggs as well.

Swedish opposition to drugs like antibiotics in

animal food production has also helped keep resistant

bacteria at bay in this country, while in many other

countries these bacteria are becoming increasingly

evident, resulting in the spread of severe pneumonia,

salmonella and tuberculosis.

In fact, Sweden has helped bring the issue onto the

EU agenda and the idea of a ban on antibiotics as growth

promoters is now widely supported. The World Health

Organization, WHO, is showing concern and at the end of

1998 the European Commission surprised many people by

banning six out of ten antibacterial feed additives. In

June 1999, all EU countries pledged to step up controls

on the non-medical use of antibiotics in animal feed.

On the hormone front, consumers and almost all

producers in Sweden have vociferously opposed the

introduction of monster cattle like the Belgian Blue.

The defect gene introduced by the breeder generates

severe problems at calving, a weak skeleton and other

disorders, and Swedish opposition has centred on the

animal welfare problems involved rather than any

potential health hazard to the end-consumer.

Genetically modified food

Genetically modified organisms (GMO) are allowed in

Sweden but in accordance with EU rules any foodstuffs

containing them must state this on the label. The

National Food Administration is working on a control

system to check compliance but proper laboratory

analysis is not yet available, although reliable methods

are being developed around Europe.

KRAV, however, does not accept GMOs in ecological

food production, and seeks to check every stage of

production and distribution to ensure that they do not

enter the food chain. Even food additives like soya

lecithin, citric acid, enzymes and vitamins are

screened. If upon inquiry the supplier or producer

cannot guarantee that the product is GMO-free, it is not

approved.

KRAV's main concern now is that test growing of GM

crops like oilseed rape may lead to modified genes

spreading via weeds to surrounding fields.

Eco-meals on wheels

Today, though, as KRAV happily notes on its website (http://www.krav.se/),

Sweden is a country where all train restaurants serve

ecologically-certified meals, all Members of Parliament

can have a KRAV-certified meal at the parliamentary

restaurant in Stockholm and McDonald's serves ecological

milk.

In terms of the percentage of total agricultural

land used for ecological farming, Sweden is now second

only to Austria, a country whose alpine terrain makes

large-scale conventional farming more or less

impossible. And in several other European countries,

including Britain and France, growth in actual

ecological production has either slowed or stagnated.

Should the spread of ecological land in Sweden be

matched by a willingness among farmers to produce

ecological primary products - a prerequisite for the

more highly processed food products that are

increasingly in demand - and should a more sophisticated

chain of supply be developed to satisfy consumer

requirements, analysts believe the `greening' of Swedish

agriculture will continue apace.

As the third millennium approaches, the arrival on

the international scene of a new Swedish model as famous

as the first one, based on a government-backed push for

the `world's cleanest agriculture', seems a fairly

realistic proposition.

The term `ecological' is used in this article - and

indeed in Sweden - in preference to the terms `organic'

or `natural' more commonly used in English-speaking

countries to describe such produce. In Sweden,

ecological produce is a catch-all label for certified

naturally grown, organically-biologically grown or

biodynamically grown produce.

Stephen Croall is a freelance journalist and

translator living in Sweden. He has specialized in

environmental issues and is the author of Ecology for

Beginners, which has been translated into 14 languages.

Educated at a vegetarian boarding school in England, he

has cautiously begun eating game in later life.

|

|

|

|

Click HERE for

FoodFromSweden.com.

A wonderful collection of details from Judith at the Swedish

Kitchen. Click for MORE.

Welcome

Welcome to A Swedish Kitchen, a website devoted to Swedish food,

both in Sweden and abroad.

Look for my new book A Swedish Kitchen:

Reminiscences and Recipes to be published Fall 2004 by Hippocrene

Press.

This page is designed and maintained by Judith

Pierce Rosenberg . I am the author of A Question of Balance:

Artists and Writers on Motherhood (Papier-Mache Press), a collection

of interviews with 25 well-known women in the arts, including Ursula K.

Le Guin, Dorothy Allison, Linda Hogan, Elizabeth Murray, Rita Dove, and

Faith Ringgold. For the past 20 years, I have also worked as a freelance

journalist, contributing to such periodicals as Ms. Magazine, The

Radcliffe Culinary Times, Publishers Weekly,The Boston Globe,The

Christian Science Monitor,The Middle East Magazine, and Fiberarts,among

others.

The new book is a memoir about my experiences with Swedish food. My

love affair with this cuisine began more than two decades ago when I

first visited Stockholm with my Swedish-American boyfriend, now husband.

I have returned to Sweden a couple of dozen times and, for the past

fourteen years, I have spent part of each summer in the Stockholm

archipelago. Over time, I have learned to speak Swedish and to cook

Swedish, which brings me to this website.

This site will include anecdotes from my own experiences in Sweden

and with Swedish food, as well as information on ingredients, holidays,

and dining customs, and reviews of interesting restaurants, books,

magazine articles, and websites. I also want to hear about what

interests you, dear reader, so please feel free to send a recipe for the

recipe exchange or email in your own anecdotes and cooking tips.

Bulletin Board :Please submit comments, recipes, or questions to our

new bulletin

board .

More Recipes

A Bit of Culinary History:

The Swedish word, pepparkakor,

literally translates as pepper cakes. The first pepparkakor were honey

cakes, flavored with pepper and other spices such as cloves, cardamom,

cinnamon and anise, and were imported from German monks beginning in the

1300s. Over time, the pepper was eliminated from most but not all

Swedish pepparkakor recipes and honey was replaced by beet sugar syrup.

Today, Swedes buy gingersnaps year-round from bakeries and grocery

stores. But for many families, baking pepparkakor at home, using cookie

cutters shaped like Christmas goats, pigs, angels, hearts, stars, men

and women, remains an essential part of the Christmas festivities.

Strömma Canal in December light. (Click on picture to enlarge)

Strömma Canal in December light. (Click on picture to enlarge)

Recipe Please e-mail any

suggestions you may have.

Books:

“Det dukade bordet” (“The set table”) by Kersti Wikström.

Written by a curator at Stockholm’s Nordiska Museet, this book has to

do with special occasion table settings in upper class homes from the

1500s to the end of the 19th century. Following a museum exhibition on

the topic, the book goes into more detail, covering the kitchen and

cookbooks of the period. Wikström has included a special occasion menu

from each century, with accompanying recipes, for those readers who want

to recreate an historic meal. The illustrated book is available in the

museum’s gift shop for 250 kronor.

Websites:

www.svt.se/malmo/aspegren

For those who can read Swedish, this site offers recipes and wine tips

from chef Rickard Nilsson who together with his younger brother, Robert

“Bobo” Nilsson, runs a restaurant in Torekov called Kattegatt

Gastronomi & Logi. The show’s host is Jesper Aspegren. You can

even write in for help with cooking problems.

www.ica.se This website, run by the

publishing company ICA, offers seasonal recipes for those who can both

read Swedish and use the metric system. This publishing company is a

subsidiary of ICA Handlarnas AB, Sweden’s largest retail grocery store

association.

www.bridgetosweden.com

Marie Louise Bratt leads tours for Swedish-Americans, taking them to the

villages and farms where their Swedish ancestors once lived.

She also helps her clients contact those relatives still living in

Sweden today.

www.kingarthurflour.com

King Arthur Flour has a great baking supply catalogue with many items

that are particularly useful for Swedish cooking. The catalogue and

baker’s help line can also be reached at 1-800-827-6836.

www.operakallaren.se

This site, in English and Swedish, includes three restaurants housed in

Stockholm’s Opera House: the sumptuous Operakällaren; the less formal

Cafe Opera; and the smallest and least formal Bakfickan, literally back

pocket. See below for reviews.

Restaurant Reviews

MORE

Swedish Food links from Google.

|

Strömma Canal in December light. (Click on picture to enlarge)

Strömma Canal in December light. (Click on picture to enlarge)